It will bring more of Russian corruption into Europe.

The most vivid evidence of Gazprom’s use as a political and corruption tool within Europe has been revealed through an antitrust investigation against it that started in eight EU countries in 2011. The European Commission filed charges in 2015 and denounced Gazprom with the illegal partitioning of EU markets, denying third-party access to gas pipelines, and unlawful pricing, all of which aimed at strangling politically and economically Central and Eastern European countries. In 2018 Gazprom managed to make a deal with the EU on the outcome of the investigation without hefty fines, promising a reformed approach. However, this does not negate past corrupt behavior, plus many EU members saw the deal as too lenient on Gazprom.

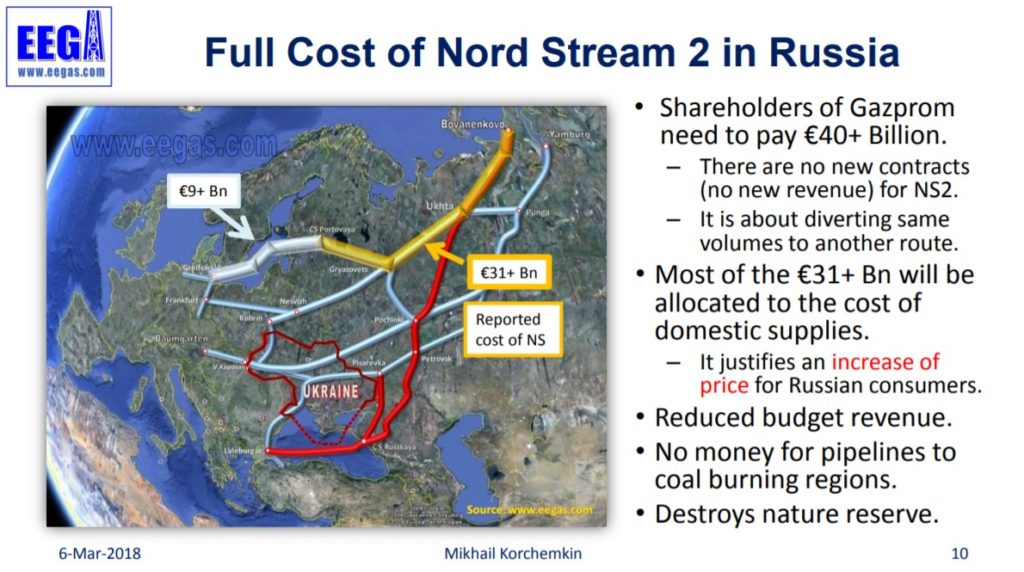

Source: East European Gas Analysis

Corruption stories surrounding Nord Stream 1 and 2, Gazprom and Putin’s inner circle prove that the more money Kremlin gets, the bigger is the reduction of democracy in Russia. Dutch public should be informed that both Nord Stream 1 and 2 were implemented at the direct loss to the Russian budget, taxpayers and environment, and the damage will be growing further, not reducing over time.

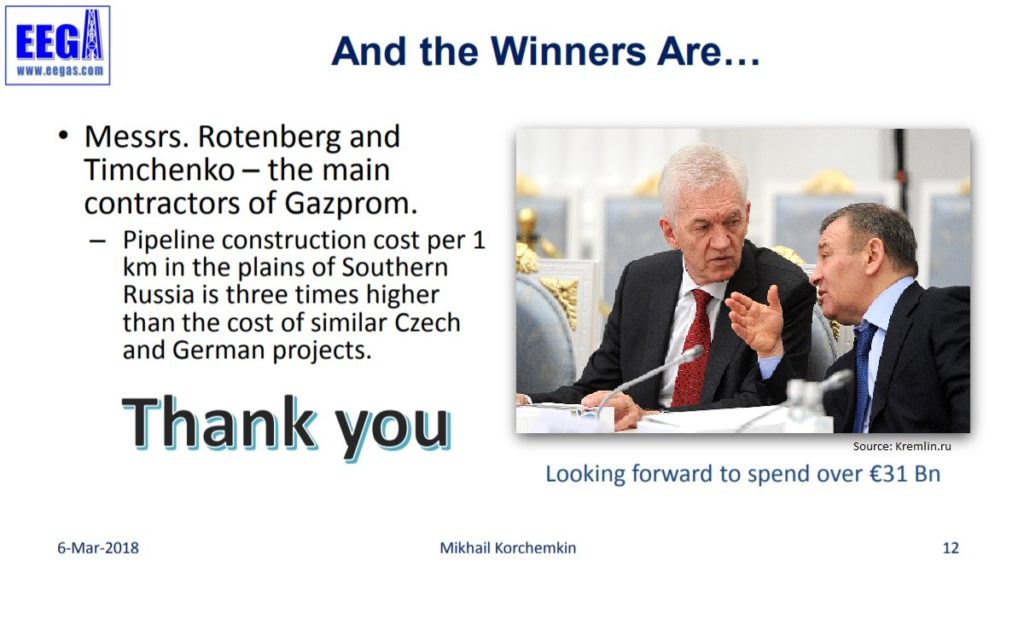

As for the pipeline directly, Putin insiders Arkady and Boris Rotenberg have been the main beneficiaries of Nord Stream 1 inside Russia. Between 2003 and 2006 their firms acted as artificial intermediaries in the sale of the trunk pipeline from Chelyabinsk pipeline plant to Gazprom. In 2007 they opened the Nord Stream Pipeline Project company, which became the main intermediary for the re-sale of pipelines for Nord Stream 1, bringing around $1bn of profit between 2008 and 2012. Eventually Russia’s Anti-Monopoly Agency acted against this scheme but only after the construction and money transfer for Nord Stream 1 was finished. Gennady Timchenko and Rotenberg brothers continue to benefit heavily from Gazprom murky schemes in production and transportation of gas, including for Nord Stream 1 and 2.

Source: East European Gas Analysis

In 2008-2016 top Russian officials, including head of the Moscow Nord Stream 1 office, and mafia bosses bought and controlled Nordic Yards, shipbuilding dock in the electoral district of Angela Merkel in East Pomerania where they ran their money-laundering and other corruption schemes. One of the shadow co-owners Aslan Gagiyev is now tried in Moscow for over 60 murders, including related to the Yards, while the other mafia boss Gennadiy Petrov is a top fugitive from Spanish courts residing in total safety in his own luxury palace in St. Petersburg.

Alexey Miller has been implicated in various corruption stories long before he became CEO of Gazprom, including in the corrupt port of St. Petersburg in late 1990s. In 2001, Miller soon after becoming CEO, carried out his first major aggressive corporate raiding campaign when Gazprom, at the instigation of Putin, gained control over the privately-owned petrochemical company Sibur. In the following years, Gazprom, using similar “administrative leverage” (i.e. the backing of Putin’s security services, law enforcement and courts), gained control over many gas industry assets: Vostokgazprom, Zapsibgazprom, Nortgaz, and many others, often at prices much lower than the market price. Since 2005 the minority shareholders of Yukos have filed multiple lawsuits against Miller and Gazprom for illegally nationalizing parts of the company. In recent years, the Court of Arbitration of The Hague satisfied some of these claims, and as a result Gazprom announced the threat of seizure of its assets.

There have been numerous cases where Miller allowed Gazprom to buy and sell assets at a great financial loss to the company, including Gazprom neftekhim Salavat (GNS), Transinvestgaz, Sibneft, and many others. The most notorious story of enriching Putin’s insiders with such price manipulation and controversial loans has been the gradual transfer of a stake of over 20% in Sibur to Putin’s son-inlaw, Kirill Shamalov, through another Putin crony, Gennady Timchenko. Shamalov, his father, and Timchenko have been Putin’s closest associates, and they have received numerous lucrative assets and contracts from Gazprom and other state companies in Russia and are beneficiaries of some of the projects surrounding expansion of Russian gas system for NS1 and 2.

If one looks at Gazprom’s Board of Directors or Management, it actually requires a considerable effort to find a single top manager not implicated in any major corruption scandal:

- Andrey Akimov, Board member: in 2003 Gazprombank controlled by him created Centrex group of companies that engaged in controversial gas sales in Europe. In 2005 European Commission noted that managers of Centrex have inappropriate close business relations with Gazprom management. After Panama Papers were revealed, Swiss authorities banned Gazprombank from attracting new clients for its money-laundering operations, including with Putin’s friend cello player Sergey Roldugin. In Cyprus Akimov managed to extract 2 million euros from Laiki bank just 9 days before the authorities froze the bankrupt bank.

- Denis Manturov, Board Member: one of the openly wealthiest Russian ministers was seen doing insider contracts in his previous as a director of a helicopter plant. He has also been noticed as a protégé of Putin’s friend Sergey Chemezov, CEO of Rostec Corporation, and involved in many controversial businesses in the defense sector.

- Dmitry Patrushev, Board Member: Son of Putin’s close KGB associate Nikolay Patrushev, Dmitry was appointed to manage Rosselkhozbank, a key state agricultural bank. Under his leadership the bank lost around several billion dollars, including in deals with partners of his father, but the bank was compensated at the expense of the Russian budget.

- Mikhail Putin, Management Committee Member: Vladimir Putin’s cousin was brought to Gazprom through nepotism. For many years he was a key figure in SOGAZ, insurance company run by Putin’s confidants which has benefited from multiple insider deals.

- Kirill Seleznev, former Management Committee Member: Seleznev worked for Miller in St. Petersburg’s port where a lot of corruption scandals took place. He oversaw insider deals on condensate trade between Kazakhstan and Gazprom that benefited unnecessary intermediaries with $4 billion. He was also seen as the main insider in corrupt transactions around Gazenergoprombank. This year Seleznev stepped down from Gazprom amid arrests of corrupt senator and his father, Seleznev’s advisor, involved in the murky gas trade in the Russian Caucasus. Seleznev is now CEO of a company building Baltic LNG terminal, a partnership with Gazprom, oriented towards Europe

There are many other corruption stories that have been uncovered by international and Russian media and activists, including the late Boris Nemtsov and current opposition leaders Alexey Navalny and Vladimir Milov. However, what matters probably the most in relation to NS2 is the deliberate unwillingness of Western policy-makers and corporations to notice corruption that accompanied the construction of Nord Stream 1 and is now clearly linked to NS2.

In May 2018 analysts from Sberbank CIB Alex Fak and Anna Kotelnikova issued a research on the Russian oil and gas. The head of Sberbank German Gref fired Fak for the research and brought apologies to Gennady Timchenko and Arkady Rotenberg – Putin`s cronies who were named as a beneficiaries of the Gazprom pipeline construction strategy in the report.

The main points from the Sberbank CIB research are the following:

- Gazprom`s investment program can best be understood as a way to employ the company`s entrenched contractors at the expense of shareholders. The three major projects that will eat up half of the capex in the next five years – Power of Siberia, Nord Stream2 and Turkish Stream – are deeply value-destructive. (page 3)

- It is commonly believed that the Russian government has been forcing Gazprom to construct the major Ukraine by pass routes, Turkish Stream and Nord Stream-2. After all, because they reach no new markets, these routes entail no marginal revenue whatsoever. Whatever benefit they derive comes from savings on transit costs, but their main rationale is a geopolitical one – to by-pass the existing Ukrainian system. (page 9)